What is Orientalism? The term Orientalist – meaning someone who is knowledgeable about Oriental people, their languages, history, customs, religions and literature – also applies to Western painters of the Oriental world. For these artists – whose numbers grew rapidly in the early nineteenth century – the Orient meant first of all the Levant. It then included Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Palestine and the North African coast. Spain, because of its Arab past, and Venice, because of its historical connections with Constantinople, were viewed by many as the gateway to the Orient. Only a few particularly adventurous artist-travellers went to Arabia, Persia or India; as for the countries in the Far East, they were virtually closed to Westerners until the end of the nineteenth century.

Since the publication of Edward Said’s Orientalism in 1978, much academic discourse has begun to use the term “Orientalism” to refer to a general patronizing Western attitude towards Middle Eastern, Asian and North African societies. In Said’s analysis, the West essentializes these societies as static and undeveloped—thereby fabricating a view of Oriental culture that can be studied, depicted, and reproduced. Implicit in this fabrication, writes Said, is the idea that Western society is developed, rational, flexible, and superior.

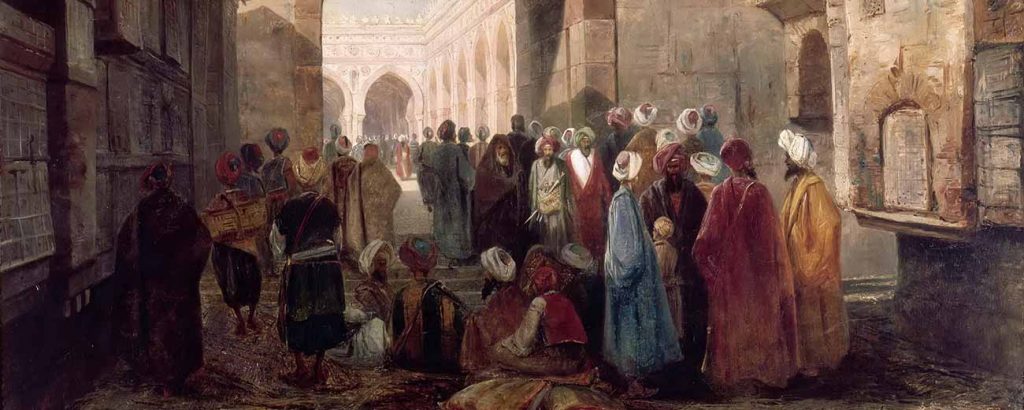

There was no school of Orientalist painting; the pictures were linked thematically rather than stylistically. Technique, especially in the treatment of light and colour, evolved with each decade, as the artists’ experiences grew. This evolution can be seen clearly in the works illustrated here, which are presented in the chronological order of their authors’ travels. There is a century – as well as a whole world of discovery and better understanding of the Orient – between the dark impasto of Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps and the delicate watercolour washes of Augustus Osborne Lamplough.

Orientalism and Academic Manner

But since many Orientalists worked in the academic manner of their time (when the “well-drawn” and the “well-painted” were highly admired), they were virtually wiped off the slate of history when academicism became unfashionable, ousted by the avant-garde. What had fallen from favour was not the Orient, it was the old manner of painting it. Only over the last decade or so has Orientalism, once known worldwide, begun to surge up again into the consciousness of art historians, dealers and the public. Paintings have reappeared in salerooms and galleries and emerged from museum basements, while exhibitions have again been held. Partly due to the general reassessment of the last century – the ridiculous has again become the sublime – as well as to a renewed esteem for technique, Orientalism has again come back into favour.

This is certainly not a passing fashion, but a natural return, in the ever revolving cycle of taste, of a justified appreciation of paintings that are marvellous invitations, visually, and through the imagination, to journeys to other lands and other times. Colourful, sunlit, strange, sanguinary, tender or instructive, they enchant and fascinate us as they did former generations. Each has its story to tell, of travel and adventure, sights and customs now changed forever, of the gradual lifting of the veils of myth and mystery in which the Orient had been shrouded, and of the heady discoveries of exoticism by Westerners accustomed to the greyness of the northern industrialized cities.

The Origins of Orientalism

Many meeting points had, of course, existed between the Orient and the Occident before the nineteenth century, through a long history of mercantile, diplomatic and artistic relations. Examples include the Crusades, the close links between Venice and Turkey, Britain’s establishment in India and France’s use of commercial ports in the Levant. But, with the exception of European artists settled in Constantinople (described by A. Boppe in Les Peintres du Bosphore au Dix-Huitieme Siecle) (Paris 1911), Orientalism had been nearly exclusively decorative. Chinese, Japanese and Turkish culture and a general hotch-potch of “Eastern” styles influenced clothes, architecture and works of art.

The storybook entitled The Thousand and One Nights, popularly known as The Arabian Nights, helped spread the vogue for exoticism, which still had no particular regard for exactitude.

The passion for Egyptology at the end of the eighteenth century, the founding of schools of Oriental studies and, most importantly, Napoleon Bonaparte’s expedition to Egypt in 1798, brought the East into public view. The illustrated albums by the baron Dominique Vivant Denon of this survey of ancient and modern Egypt, as well as the Napoleonic history paintings in Oriental settings by the baron Gros, Anne-Louis Girodet-Trioson and others, laid the foundation for the Orientalist movement.

Journey to the Orient

The Greeks’ struggle for independence from Turkish rule, the Romantics’ espousal of their cause, the taking of Algiers by the French in 1830 and Delacroix’s only too famous journey to Morocco in 1832 all helped open wide the doors to hundreds of artists who were to make the journey to the Orient. Travellers and stay-at-homes alike often relied heavily on literary sources for their works. These were generally fiction, such as Lord Byron’s Turkish epics, Thomas Moore’s Indian romance Leda Rookh, Gustave Flaubert’s Salammbo, Theophile Gautier’s Le Roman de la Momie and Victor Hugo’s Les Orientales. In addition, there were the recitals of their journeys, by influential writers and poets, including François-Rene de Chateaubriand, Alexandre Dumas Pere, Gerard de Nerval, Alphonse de Lamartine and Gautier.

Political Interest

Though British political interest in the territories of the unravelling Ottoman Empire was as intense as in France, it was mostly more discreetly exercised. The origins of British Orientalist 19th-century painting owe more to religion than military conquest or the search for plausible locations for naked women. The leading British genre painter, Sir David Wilkie was 55 when he travelled to Istanbul and Jerusalem in 1840, dying off Gibraltar during the return voyage.

Though not noted as a religious painter, Wilkie made the trip with a Protestant agenda to reform religious painting, as he believed that: “a Martin Luther in painting is as much called for as in theology, to sweep away the abuses by which our divine pursuit is encumbered”, by which he meant traditional Christian iconography. He hoped to find more authentic settings and decor for Biblical subjects at their original location, though his death prevented more than studies being made. Other artists including the Pre-Raphaelite William Holman Hunt and David Roberts had similar motivations, giving an emphasis on realism in British Orientalist art from the start. The French artist James Tissot also used contemporary Middle Eastern landscape and decor for Biblical subjects, with little regard for historical costumes or other fittings.