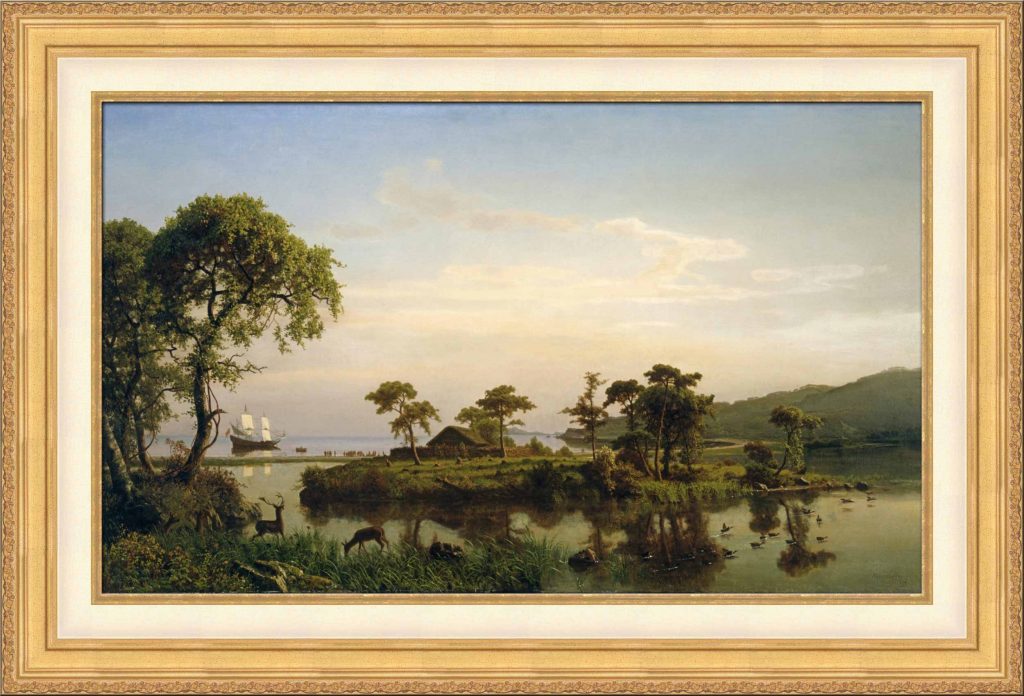

Albert Bierstadt Gosnold at Cuttyhunk

Date: 1858

Technic: Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 71 x 124 cm (28 x 49 in.)

Location: Old Dartmouth Historical Society Whaling Museum

Art Movement: Hudson River School

Bartholomew Gosnold (d. 1607), the English explorer and colonizer, sailed for the New World in 1602 and eventually landed on the coast of Maine. He then worked his way south to an is-land near Cape Cod which he called Elizabeth (now Cuttyhunk), where he landed and built a fort. From this story Bierstadt fashioned a remarkable painting, considering that it was completed a little over a year after he returned from Europe. In it he records his direct response to a shoreside scene, an utterly peaceful moment on a summer day at high noon.

Gosnold at Cuttyhunk has few of the Dusseldorf mannerisms of Bierstadt’s earlier work. Gone are the clouds as well as the clotted and cluttered surfaces. In their place Bierstadt substituted a broad prospect and an open expansiveness – a quality of design he probably acquired in Italy. (For the record, Carl Lessing had painted panoramic land-scapes in the early 1850s.) To the soft, melting atmosphere of Italy, however, Bierstadt added the clear and harder light of New England, at least in the foreground.

Luminist characteristics

Perhaps he had become aware of Luminist works by artists such as Fitz Hugh Lane. In any event, Gosnold is one of the few of Bierstadt’s works to have Luminist characteristics: a low horizon line, considerable amounts of water reflecting a nearly cloudless sky, and isolated forms silhouetted against neutral backgrounds rather than clustered, superimposed detail. He also added what seem to be glazes of golden yellow to the entire surface to harmonize the elements of the painting and to emphasize the golden daylight.

But despite the Luminist qualities, certain Bierstadt traits persist. The brush strokes are visible and are more lively. Tonal contrasts of lights and darks – of sunshine and shadow – are more abrupt, as in the trees at the left. In this painting Bierstadt allowed studio lighting conditions to dominate his perception of outdoor light. The trees tend to writhe more than those of other American artists. And the colors of the hills to the right are too intense in comparison to those of Luminist works, in which distant forms are often unnaturally pale.

As in past and future works of Bierstadt, anecdotal incident is kept in the safe middle distance. It dignifies the landscape with human presence but does not force it to serve as a mere backdrop for human drama. The spaciousness of the scene, in part created by the sea merging with the sky at the horizon line, is rare in Bierstadt’s work. As pleasant as it is, Gosnold marks a false start in Bierstadt’s career. Had he persisted in exploring the compositional and coloristic ideas indicated here, he might have added a painterly breadth to Luminism; but his pictorial interests lay elsewhere.