Théodore Chassériau (1819 – 1856)

Théodore Chassériau was born in El Limón, Samaná. Chassériau’s father, a government official who led an unstable and roaming life, brought his family to Paris from the West Indies in 1822. He left, alone, for South America, while Théodore’s mother, the daughter of a French colonial landowner, returned home. The children were brought up by their elder brother, Frédéric. Théodore became a pupil of Ingres at an early age. Ingres had an enormous admiration for his talent, and invited him to Rome on his nomination as director of the French Academy, but Chassériau preferred to work on his own.

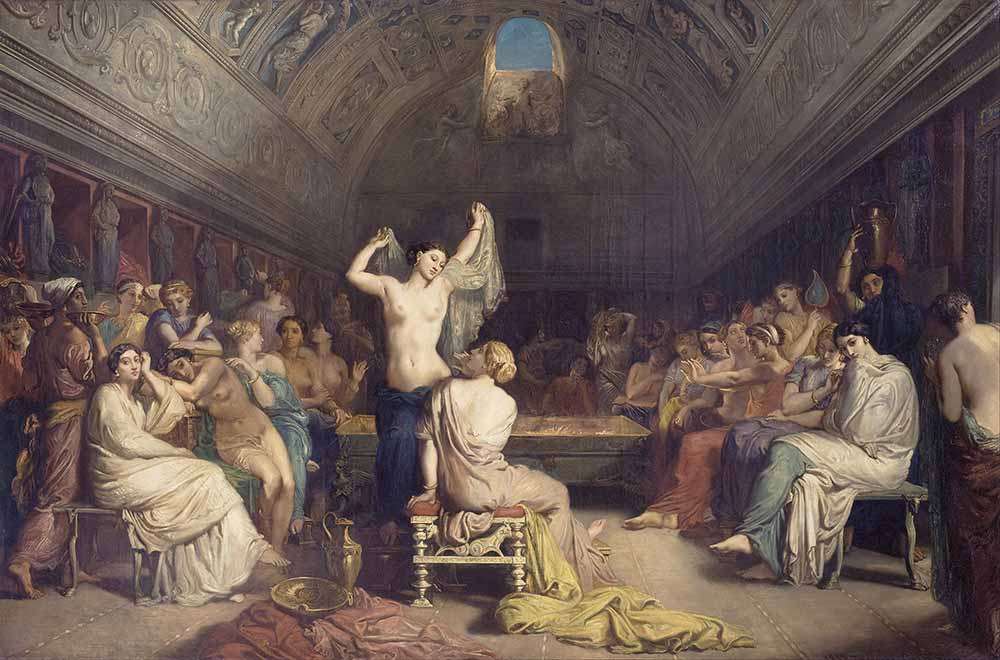

He began his career with portraits and biblical and classical subjects, such as Suzanne, shown at the 1839 Salon and Esther Dressing in Finery to meet Ahasuerus (Musée du Louvre, Paris). These sensuous nudes, imbued with all the poetry of the Orient, show Chassériau’s already developed taste for exoticism. At the time, a lot was written about this Creole’s nostalgia for his native island, but it is more likely that this inclination was due to his adulation of Delacroix and his friendship with Prosper Marilhat, Théophile Gautier and Gérard de Nerval. In 1843, he finished a commissioned mural for the church of St. Merri in Paris, in which his scenes from the life of St. Mary the Egyptian were a blend of classical and Oriental antiquity.

commissions

Another commission, to paint the portrait of Ali ben Ahmed, caliph of Constantine, proved to be a turning point in his career. This picture was shown at the 1845 Salon, at the same time as Delacroix‘s very similar portrait of the Sultan of Morocco, Moulay Abder Rahman. Chassériau had become quite friendly with the caliph during his stay in Paris, when his unusual appearance caused a sensation in the streets and at the opera. This acquaintanceship led to an invitation from the Algerian leader to visit his stronghold of Constantine. On his arrival in May 1846, Chassériau found that this astonishing town, perched on a sheerwalled crag, was filled with “invaluable treasures for an artist.” ”The country is lovely and brand-new,” he wrote. “I am basking in the land of The Thousand and One Nights.” He was fascinated by the varied ethnic types and saw “the Arab and Jewish races as they had been at the time of their earliest origins.”

He spent the rest of his two-month stay in Algiers. Although the city was too “Frenchified” for his taste, he was captivated by the light and beauty of the tones of the sky and sea. The landscape scarcely interested him as an artist, however; instead, he feverishly made sketches of people, in both pencil and watercolour. Like Delacroix, he found it was easier to enter Jewish than Muslim households, and it was amongst this community that he found most of his models.

Théodore Chassériau was Refused

His first major Algerian work was The Sabbath in the Jewish Quarter of Constantine, an enormous canvas that was destroyed by fire before any record could be made of it. The painting was refused at the 1847 Salon, but it was shown at the juryless Salon of 1848, where it was enthusiastically received by Théophile Gautier, one of Chassériau’s most ardent admirers. He was not able to return to Algerian subjects until 1849, since he was obliged to finish the decoration for the Cour des Comptes, one of his many monumental religious and allegorical decorations for public buildings in Paris. By then, three years after his journey, his fading memories had become distilled into idealized images.

Chassériau had made many studies of Arab horses in Algeria and these are the focal point of such lively pictures as Arab Horsemen carrying away their Dead (Fogg Museum of Art, Cambridge, Massachusetts), Arab Horsemen in Combat (Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, Massachusetts) and Arab Chieftains challenging each other to Single Combat (Musée du Louvre, Paris). Other pictures were solemn and melancholic scenes of domestic life, such as Constantine Jewesses on a Balcony (Musée du Louvre, Paris), Moorish Woman suckling her Infant and Two young Constantine Jewesses rocking a Child.

Died at the age of thirty-seven

As for his sensual nudes, for which he posed Parisian models, Moorish Woman Emerging from the Bath, Recumbent Odalisque, Oriental Finery and Interior of a Harem, these evoked an Orient as imaginary and fantastic as the one he painted before his African journey. Chassériau had suffered from bouts of physical weakness since 1852, but when he died at the age of thirty-seven, the art world was stunned. Gustave Moreau began studies for a painting in tribute to him, entitled The Young Man and Death, now in the Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Symbolising the fragility of success in the face of death, it was shown at the 1865 Salon. Many of Chassériau’s paintings and sketches were donated to the Musée du Louvre by his great-nephew, the baron Arthur Chassériau.

Théodore Chassériau’s Orientalist pictures combine the neoclassical idealization of Ingres and the emotive use of colour of Delacroix. Painted with sensibility and great intensity, they are amongst the most personal visions of the Eastern world.

Literature: A. Bouvenne, Théodore Chassériau, souvenirs et indiscrétions, Paris, 1884 ; V. Chevillard, Un peintre romantique, Théodore Chassériau, Paris, 1893; H. Marcel, L’Art de notre temps: Chassériau, Paris, n.d.; L. Bénédite, Théodore Chassériau, Paris, 1931; M. Sandoz, Théodore Chassériau, Catalogue Raisonné des Peintures et des Estampes, Paris, 1974.

SEE CANVAS PRINT GALLERY FOR THIS PAINTINGS